Born in Chișinău in 1920, Valentina Rusu Ciobanu is one of Moldova’s most visionary artists. Neither a dissident, nor a conformist, Rusu Ciobanu spent her career as a free spirit who always stayed loyal to her own artistic explorations. Now turning 100 on 28 October, she has gained both respect and recognition for her painting practice. Four exhibitions are currently celebrating her centenary: at the National Museum of Art between 28 October-13 December and the National Museum of Literature in Chișinău between 28 October-10 January, at the Museum of Bucharest Palace Șuțu between 5 – 29 November, and at the independent Arbor gallery in Bucharest between 28 October – 29 November.

Early defining moments

Living in her hometown for most of her life, Rusu Ciobanu has experienced a century’s worth of change, throughout which she has been a citizen of Romania, the USSR, and, now, the Republic of Moldova. She lived through the Second World War, the famine of 1946–1947, and the fall of the Iron Curtain. Yet, when asked about her wealth of lived experiences during an interview in September, she recalls, above all, the ordinary moments of extraordinary significance which she chronicled with her paintbrush — the routines of rural life in Moldovan villages, the warm hearts of the people who welcomed her there, the food the local women shared, and the gossip they indulged in. “People are all the same,” she says, an observation which she unravels with a story.

“At one time, I painted the sons and daughters of collective farm residents, the housewives,” Rusu Ciobanu recalls. Her 1957 painting At the Dances, was produced over several trips to the village of Dolna, situated 60 kilometres north-west of Chișinău. “There was a village legend that whichever young person I painted would get married the following year. So I was inundated with requests for portraits,” she laughs. At the Dances, like many other paintings by Rusu Ciobanu, were commissioned by Moldova’s Union of Artists. Still, her work was met with disapproval by some officials, for not being realist enough and taking its characterful brushstrokes from Formalism and Impressionism.

Indeed, Rusu Ciobanu’s 1950s paintings take inspiration from the works of the late 19th-century Romanian painter Nicolae Grigorescu, who introduced Impressionism into his country. This painting style was passed onto her from her teachers in Moldova — among them the French painter August Baillayre and her tutor at the Romanian Institute of Art in Iași, Corneliu Baba, who would later become a famous portraitist.

One of her best-known works from this decade is the 1954 painting Girl at the Window. It features her neighbour, dressed in a traditional Moldovan/Romanian costume, borrowed from the Ethnographic Museum in Chișinău. Rusu Ciobanu was photographed wearing this traditional costume that very same year at a conference in Kyiv, surrounded by men and women dressed in dreary city clothes — an image that has come to stand for her confidence and individuality. Following Stalin’s death, art was to be “socialist in content and national in shape” according to Soviet authorities, and Rusu Ciobanu made the most of this newly opened door.

Defining works

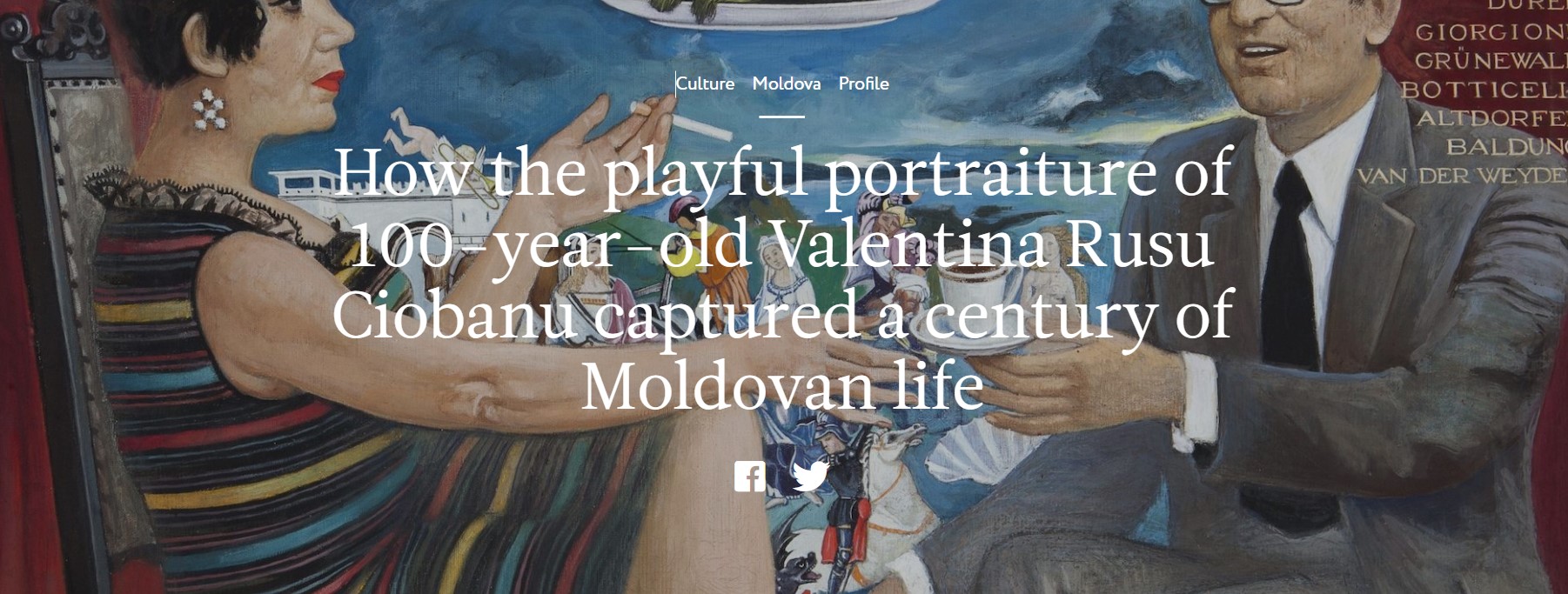

It was during the 1960s–1970s that Rusu Ciobanu really found her style, producing daring and original paintings. Her state-commissioned portraits of Moldovan authors and filmmakers show the ways in which the painter embraced elements of naive art, surrealism, and expressionism, along with playfulness and humour. These works reveal a free-wandering, cosmopolitan mind. There are robots, meta references, and experiments with perspective — all of which, according to the artist, helped her “unlock the character of each sitter”.

Beyond painting

Rusu Ciobanu was an avid reader. While no translation of James Joyce was available in Romanian or Russian at the time, the artist read the literary giant in English, which she taught herself. Her son Lică Sainciuc, now an artist, remembers their family home always being full of Polish and Romanian art magazines, which were only available in the early 60s before being banned by the end of that decade, as protest movements gained prominence in Poland. Instead of taking her son to see Soviet films, Sainciuc recalls his mother finding Western cartoons and films, which were only available to watch in the smaller cinemas in Chișinău. Artists and writers were regular guests in their home — a 19th-century, one-storey house in the historical centre of Chișinău, with its own garden.

Her home was her creative bubble. Outside its walls, she stood her ground. “Sometimes I remember something that makes me think that I was stupid. But other times I got what was going on,” she says of her defiance of political and ideological demands. She admits that she was “more interested in other people’s attitudes [to politics] than her own.” At one Artists’ Union meeting in the 1960s, she openly said that she did not support an official’s re-election because he was not “principled” and a “liar”. Spurred by the artist, the whole room then voted against his candidacy.

Legacy

Rusu Ciobanu constantly navigated the tide between being promoted as an artist, and then being shut down by the authorities. In 1983, the National Museum of Art in Moldova hosted a major retrospective dedicated to Rusu Ciobanu. Although the show was popular with the public (because her style was not aligned with the ideology of the party) exhibition reviews were only allowed to be published in newspapers outside of Chișinău, where they would be read by people who hadn’t seen the works. After several cultural figures expressed their outrage at this unfair treatment of Rusu Ciobanu, one review was finally published in a national arts magazine, but with no pictures illustrating it.

Things have changed since Moldova’s independence. A big poster of one of Rusu Ciobanu’s paintings from 1980 can be found adorning the exterior of the National Art Museum in Chișinău. The work has a simple title, Breakfast, yet its composition is exquisite. Rusu Ciobanu’s sister posed for the painting, which shows her daydreaming next to a table with lilacs, daffodils, tea, fried eggs, and toast. “I gathered my most beautiful crockery to paint it,” Rusu Ciobanu says. The only fictional item in this painting is the tablecloth. “It is a tablecloth I’d dreamed of, since I did not possess such a beautiful fabric.” The artist gives the landscape outside the window the gravitas of high Renaissance art — something she repeats in her 1978 painting The History of Art, which abounds in references to iconic paintings.

Breakfast remains one of Rusu Ciobanu’s favourite artworks because it surprised her in the creation process. She says there’s a joy in “thinking a work would turn out one way but ending up as something different”.

The artist stopped working a few years ago, when she realised the process strained her eyes. “When I used to work, all of my paintings were dear to me. But now that I can’t see them anymore; I don’t like any of them,” she adds. Yet, since getting cataract surgery, she is able to distinguish colours a bit better. At 100, she boasts she is the first in her family to spot the violets when they pop up in spring.

This article is part of our series Women, Recollected, an ongoing project shining a light on the forgotten women pioneers of 20th century culture.